What is Madingley?

The scientific community has spent decades developing models of the atmosphere and climate so that we can project the consequences of anthropogenic climate change. But there is no equivalent for life on land and in the sea. Madingley was developed with exactly this long-term vision in mind: to develop a model of ecosystems and biodiversity on land and sea that would follow on from the successes of climate models and use the fundamental principles of how animals and plants interact to project the global consequences of human impacts.

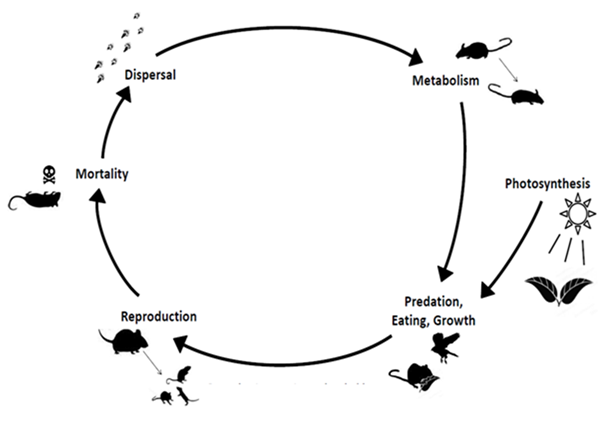

The Madingley model is an entirely new approach to modelling ecosystems and biodiversity. It is different from existing models as it includes both marine and terrestrial ecosystems, and marine and terrestrial human pressures – fisheries, agriculture, and climate change, for example. It is global in scope but can be applied regionally or nationally, and allows for unpredictable behaviour to emerge – meaning that food webs can shift and ecosystems can radically alter. It is published and described in the scientific peer-reviewed literature, and is open for anyone to use and modify.

The aim of the Madingley model are two fold. Firstly, to provide decision makers with the knowledge and information that they need in order to ensure global sustainability goals and policies are achieved. Secondly, to provide scientists, academics, and researchers with a new type of modelling tool that can be used to answer questions of fundamental ecological importance that were previously not able to be tackled. Ecosystem models need to be as sophisticated and useful as climate models – and Madingley is a step towards this.

What can it do?

The Madingley model was developed to answer fundamental questions about achieving sustainability. The model can explore how ecosystems and the services that they provide will respond in a future of record human population density, a warming climate, increasing natural habitat conversion and fishing effort. It is still under development – climate models have evolved over more than 50 years – but we have a vision of the types of policy decisions that Madingley could answer.

The model’s global nature means it is potentially capable of answering questions of food security, such as capturing trade-offs between agriculture and fisheries. It can help us to understand the ‘tipping points’ or boundaries – regional or global - beyond which further human pressure will cause ecosystem collapse and loss of function. It can be used with existing climate scenarios and socio- economic projections to help understand changes to ecosystems at local or global scales.

These are just examples of what we can do with Madingley. Other potential questions include:

- Effects of nutrient run-off from agriculture and pollution on marine ecosystems

- Understanding how ecosystem response to stressors varies by region

- Back-casting from desired outcomes to understand the trajectories that may take us there

Our goal is to explore the interactions between humans and ecosystems – and the services they provide – at national, regional and global scales, and to provide robust scientific information in an easily interpretable manner.

When should I use Madingley?

There are many types of biodiversity and ecosystem models, including species distribution models, size-structured models, and vegetation-only models. It is important to fit the right model to the right question. Madingley is particularly suited for answering questions:

- At the global scale, looking at big-picture outcomes for the future of humans and biodiversity on planet earth

- Where the land and sea are coupled; such as with nutrient run-off, or with agriculture, aquaculture, and fisheries all providing a proportion of human dietary requirements

- When interactions among species are important. Many ecological or biodiversity models have limited interactions between individuals, or ‘fixed’ and balanced types of interactions. Madingley allows interactions to evolve and change over time, as the climate or human impacts alter ecosystems. This can allow the prediction of novel and unstable states

- Looking at ecosystem complexity and resilience in the face of disturbance, and whether community states can change irrevocably

- Understanding the links between pressures, states of biodiversity, and outcomes in terms of human well-being, especially as applied to international biodiversity targets such as the Aichi Targets and Sustainable Development Goals.

- When the question emphasises understanding not only how an ecosystem might change but also why that change might occur, so that the best intervention can be designed.

Madingley does not exist in a vacuum, and we have learned from and benefited from the work of others in this sphere. We recommend that potential users familiarise themselves with the array of tools available. Examples of other models of biodiversity and ecosystems include GLOBIO, Atlantis , and EcoPath with Ecosim.

Do I have to be a modeller to use Madingley? What if I am a decision-maker that needs answers?

As our aim is to assist with providing answers to pressing questions about the natural world and our effect on it, we are happy to discuss how the model can be used to answer specific policy questions. Most ecological scientists with computational backgrounds will be able to interact with the model directly; however, we are currently working on making the model more user-friendly, and the results more accessible for those outside these domains who do not want to run the model directly. If you are interested in contacting us to discuss this, please send us an email madingley@unep-wcmc.org.